Hello Again,

The draw knife is shaving hair, the spoke shave is adjusted to take translucent shavings and the sweet aroma of air-dried Yew is on the air. Somewhere out there, under a dry thatched roof, there is nervous talk of war…

Step Three: Choosing a Draw Weight.One of the most defining characteristics of the medieval war bow was its uniquely high draw weight. Just how high that draw weight was has been a matter of conjecture among archers, bowyers and historians and will likely be disputed long into the future. Estimates start as low as about 80# and go as high as 180# or more.

Arguments for low draw weight (100 lbs. or less):

1. For the most part, medieval war bows were goverment-issued equipment. Government quantities of production usually lead to standardization and the Mary Rose bows reflected this. For example, the tips were all exactly 12 mm (about 31/64”) and at one time, they all had horn nocks. If the government were issuing bows to peasant archers (often, but not always the case), every archer would be expected to be able to draw any bow, and not everyone can draw 150# bows. Thus, the bows would be tailored to the lowest common denominator.

2. The nocks on the arrows found on the Mary rose all have 1/8” slots. A hemp or linen string that would fit this size of nock would not last long on a 100# bow, and may not even last one shot on a 180# bow. Bows often break when their strings break, so it is unlikely that a 120+ pound bow would be a practical weapon if it was constantly breaking strings (or breaking).

3. 100# bows shoot very nearly as far as 150# bows. For the extra cost in broken strings and broken bows, 20 yards of extra cast may not be enough to have tempted the medievals.

4. Using the same quality of wood, and the average English war bow pattern, a 150# bow is much more likely to break than a 100# bow. Medieval archers, bowyers and kings would have known this and wouldn’t have pushed the limits more than necessary.

Arguments for high draw weight (120 lbs. or more):

1. Medieval arms race: thicker armor leads to heavier bows, which leads to thicker armor, which leads to heavier bows…

2. Even if a 150# bow doesn’t shoot much farther than a 100# bow, it still shoots farther! An extra 20 yards of cast could conceivably win the day.

3. ‘Just because we can’t make a linen or hemp string that is strong enough for a 150# bow and still fits a 1/8” nock doesn’t mean that they couldn’t.’ (That is, there was an ancient skill that is lost to us).

4. Replica bows that are made from the same materials as the originals, and to the same dimensions as the originals tend to be well over 120 lbs. Some would even say that you can’t make a replica to the same dimensions without going over 120#.

5. Since the people who were using war bows were being trained from youth, there is good reason to believe that they could work into very heavy bows by the time they are ready for military action. That is, 150# is not too much to pull for a medieval farm boy who had been shooting since infancy.

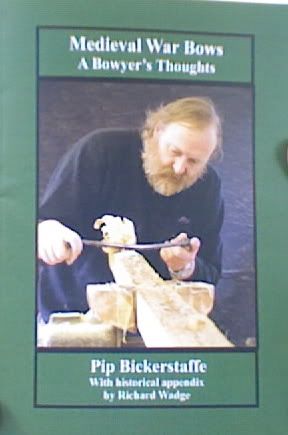

Personally, I like to think that the original bows were between 100 and 150 lbs. That’s mostly based on bowyers’ intuition. I think the arguments on either side are compelling enough to justify taking sides, but bowyers’ intuition will not be absent when sides are taken. Pip Bickerstaffe has recently published an essay (In book form, titled Medieval War Bows—pictured below) on why he thinks the Mary Rose bows were about 100# +/- a couple pounds.

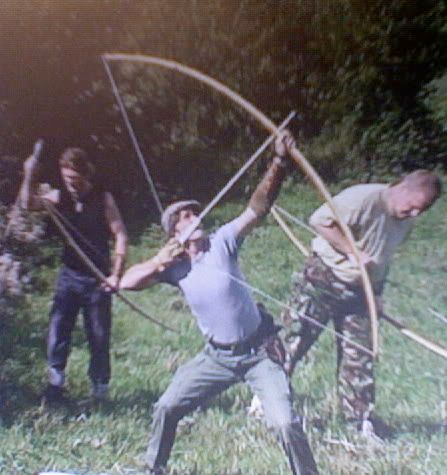

Pip is no slouch and he has done his homework. There are others who, with equal education, choose higher weights. Even one of Pip’s own replicas was longer and thinner than the average Mary Rose bows and draws 115# (Pictured below being shot by Steve Stratton).

I have chosen a draw weight of 100 lbs. for my first attempt at a war bow. I have done this for several reasons:

1. That is a weight I’ll be able to work into quickly.

2. I’m not using the best stave, and I don’t want to exceed the limits of my materials.

3. I can always build a heavier bow later—right now I'm in it to survive.

So my friends, take an honest assessment of your materials, flex your arms in front of the mirror, and dream of heavy bows and battles won.

Until tomorrow then…