|

A

while back, a good friend of mine gave me a couple of Osage billets.

These billets had been prepared by a friend of his for use in the commercial

takedown handles you can buy at some of the traditional archery supply

stores that cater to the primitive in us. The only problem with these

billets was that they had been shaped to fit the metal tube while they

were still a bit too wet. This did not work out so well because once

the Osage had dried completely, the fit inside the brass tube was too

loose and there was no way to properly remediate the situation. My friend

tried to fill the gap with glue but the pressure was too high for that

to work. This is when he asked me if I could use them and I accepted,

figuring I could make something out of them. When they arrived by mail,

I looked them over carefully and found them to be very nice with good

thick rings. They had a bit of character to them and only one of the

billets had a back ring chased down, the other was only half done. I

put them aside until I could figure out what to do with them. A

while back, a good friend of mine gave me a couple of Osage billets.

These billets had been prepared by a friend of his for use in the commercial

takedown handles you can buy at some of the traditional archery supply

stores that cater to the primitive in us. The only problem with these

billets was that they had been shaped to fit the metal tube while they

were still a bit too wet. This did not work out so well because once

the Osage had dried completely, the fit inside the brass tube was too

loose and there was no way to properly remediate the situation. My friend

tried to fill the gap with glue but the pressure was too high for that

to work. This is when he asked me if I could use them and I accepted,

figuring I could make something out of them. When they arrived by mail,

I looked them over carefully and found them to be very nice with good

thick rings. They had a bit of character to them and only one of the

billets had a back ring chased down, the other was only half done. I

put them aside until I could figure out what to do with them.

They sat

in my shop for a few months and every once in awhile I would look at

them, I guess to see if I would get any inspiration. They were plenty

long enough that I could have cut the spigot end off and cut a joint

in for splicing, but I have plenty of Osage I can do that with. The thought

crossed my mind about trying to get some metal tubing of the right diameter,

but I deduced that this would not be an easy task. Then it came to me.

Why not make a sleeve out of another non-traditional material: fiberglass.

I have used fiberglass for auto body repairs before, and it is quite

strong for its size. I had nothing to lose, plus I had all the materials

I would need on hand. Here is how I went about making this twopiece takedown.

The

limbs had been cut out on a band saw, so the first thing I did was to

clean up the saw marks from the belly and sides. The limbs were a bit

less than 34" from tips to spigot end, so they were plenty long

enough to make a bow for my drawlength, and more. They were also about

5/8" thick

by 1¼" wide so I knew I could make a bow of at least 50#

at a 28" draw out of them. I then finished chasing a ring on the

one limb. The fades had been roughly shaped so I didn’t have to

do any work on them for now. Next, I removed the dried glue from the

spigots. (photo 1): The two limbs before working

on them. The

limbs had been cut out on a band saw, so the first thing I did was to

clean up the saw marks from the belly and sides. The limbs were a bit

less than 34" from tips to spigot end, so they were plenty long

enough to make a bow for my drawlength, and more. They were also about

5/8" thick

by 1¼" wide so I knew I could make a bow of at least 50#

at a 28" draw out of them. I then finished chasing a ring on the

one limb. The fades had been roughly shaped so I didn’t have to

do any work on them for now. Next, I removed the dried glue from the

spigots. (photo 1): The two limbs before working

on them.

I have never

made a bow using the commercial metal tubes—lack of interest being

the reason—so I had no idea of their length, other than what

I had seen in pictures. I started out by laying the limbs end to end

so I could calculate how long of a handle I would need to fit my hand

comfortably. I settled on a handle length of about 5", although

I realized later on that I could have made the handle shorter. A 5" handle

however, would leave a space between the two limbs since the shaped ends

that were to be inserted into the handle piece were not long enough to

butt together. I would therefore need a spacer. I didn’t want to

leave that empty space inside the handle as this would weaken it. The

ends that had been shaped for inserting into the commercial handle were

about 2" long so I would need a spacer of about 1" to give

me the 5" handle I was looking for. I decided

to use elm for the spacer (it’s a tough wood that takes quite well

to glue) and shaped it to match the shape of the Osage ends that were

to be inserted into the handle piece.

I figured that the majority of

the pressure exerted on the handle would be on the belly, at the opening

of the handle, and back where the spigot ended with the sides of the

handle merely holding them together. I also didn’t want a round

handle but one more narrow and deep, in keeping with the general shape

of the limb spigots. With that in mind, I started cutting strips of glass

cloth. I cut a couple strips the full width of the handle and fairly

long so that I could wrap them completely around. These would be the

first pieces that I would use to establish the base of the handle. I

didn’t

want them too long though, as it would have made them unmanageable. Since

my plan was to lay a number of narrow, 1" wide strips along the

belly and back to build up some depth and add strength, I would also

need a few narrow strips, about 1" wide and long, to wrap around

the openings to secure the ends of these strips. I also cut a number

of wider ones, about 3" wide, and about 6" long to build up

the center of the handle, and also to hold down the narrow back and belly

strips. Next, I cut a large number of the 5" long and narrow pieces

that would lie down along the length of the back and belly of the handle.

I wanted to do as much of the glasswork as I could in one shot as the

resin I was going to use is quick-setting, so I tried to get as much

glass cloth cut up as I would need. I figured that the majority of

the pressure exerted on the handle would be on the belly, at the opening

of the handle, and back where the spigot ended with the sides of the

handle merely holding them together. I also didn’t want a round

handle but one more narrow and deep, in keeping with the general shape

of the limb spigots. With that in mind, I started cutting strips of glass

cloth. I cut a couple strips the full width of the handle and fairly

long so that I could wrap them completely around. These would be the

first pieces that I would use to establish the base of the handle. I

didn’t

want them too long though, as it would have made them unmanageable. Since

my plan was to lay a number of narrow, 1" wide strips along the

belly and back to build up some depth and add strength, I would also

need a few narrow strips, about 1" wide and long, to wrap around

the openings to secure the ends of these strips. I also cut a number

of wider ones, about 3" wide, and about 6" long to build up

the center of the handle, and also to hold down the narrow back and belly

strips. Next, I cut a large number of the 5" long and narrow pieces

that would lie down along the length of the back and belly of the handle.

I wanted to do as much of the glasswork as I could in one shot as the

resin I was going to use is quick-setting, so I tried to get as much

glass cloth cut up as I would need.

(photo 2): Glass cloth and resin (photo 2): Glass cloth and resin

Now that I had my materials prepared, I was ready to make the handle.

I clamped a 2x4 long enough to accommodate the length of the bow into

the vise of my workbench. After greasing the spigot ends of the Osage

limbs with Vaseline so the glue wouldn’t stick to them, I clamped

them to the 2x4, elevating them a couple of inches with small blocks.

I did it this way so I could have free access around the limbs to be

able to wrap the fiberglass cloth around the handle. I then inserted

the elm spacer in between the two limbs and drew the Osage limbs up

tight to it; the limbs held the spacer in place.

I carefully sighted

down the limbs to make sure I had proper alignment and made adjustments

accordingly. I then mixed up a quantity of polyester resin and started

by brushing some lightly on the spigots. Then, using the long full-width

cloth, I wrapped it around the handle, applying resin as needed to keep

the cloth wet. Then I applied a number of the short pieces along the

back and belly, followed by the narrow, long pieces along with the wider,

long pieces to hold everything together. It was messy work. Polyester

resin sets extremely fast (about 5 minutes), so applying all the cloth

in alternating layers was impossible to do in one application. It took

three applications (about an hour) to completely apply all of the fiberglass

and make the handle to my satisfaction.

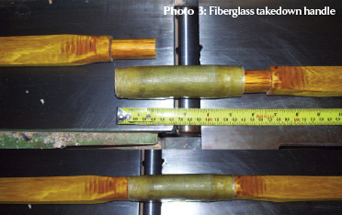

Once I was done, I let the bow

sit for a couple of hours to give the resin time to cure. Finally, I

separated the handle from the limbs: the fit was quite tight. The step

up from the spigots to the limb proper was a bit more than 1/8" and

now the fiberglass handle was pretty well flush with the limbs so that

would give it a wall thickness of at least 1/8". Once I was done, I let the bow

sit for a couple of hours to give the resin time to cure. Finally, I

separated the handle from the limbs: the fit was quite tight. The step

up from the spigots to the limb proper was a bit more than 1/8" and

now the fiberglass handle was pretty well flush with the limbs so that

would give it a wall thickness of at least 1/8".

(photo 3): Fiberglass

takedown handle

After a couple of days, I decided to start doing a bit of work to the

bow. I began by sanding the back edges of the limbs and then scraping

the belly into a shallow D section. Floor-tillering showed me that it

was strong and though I was a bit worried about the handle, I didn’t

see any flex in it while bending the limbs. I was a bit leery of the

handle as this was something entirely new to me so I kept a close eye

on it at every step. I clamped the handle of the bow into my vise, protecting

it from the steel with some wood, and applied pressure to the limb tips.

There was still no flexing of the handle or any telltale sounds of imminent

failure.

Even though the job I did with the fiberglass was pretty smooth, there

were some areas that needed to be worked on. I sanded the handle down

to give it a fairly smooth and uniform shape: I did most of this work

outside since fiberglass is toxic. The finished dimensions of the handle

came out to 1¾" deep by 1 3/8" wide

at the center and 1 5/8" deep by 1¼" wide at both ends.

After sanding the handle down, I once again clamped it in my vise and

flexed the limbs by pushing on the tips. Still no flexing of the handle,

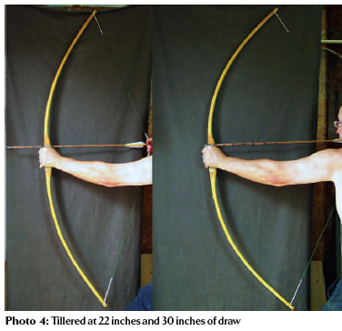

so I continued tillering the bow out. The overall length of the bow was

69" long

so I knew that I could get a 30" draw out of this bow. Tillering

the bow out was fairly easy and uneventful. I was quite concerned that

the handle would give out along the way but it didn’t give me any

indication that it was being stressed too much and easily held up to

the bow’s finished draw weight of 65# at a 30" draw. Even though the job I did with the fiberglass was pretty smooth, there

were some areas that needed to be worked on. I sanded the handle down

to give it a fairly smooth and uniform shape: I did most of this work

outside since fiberglass is toxic. The finished dimensions of the handle

came out to 1¾" deep by 1 3/8" wide

at the center and 1 5/8" deep by 1¼" wide at both ends.

After sanding the handle down, I once again clamped it in my vise and

flexed the limbs by pushing on the tips. Still no flexing of the handle,

so I continued tillering the bow out. The overall length of the bow was

69" long

so I knew that I could get a 30" draw out of this bow. Tillering

the bow out was fairly easy and uneventful. I was quite concerned that

the handle would give out along the way but it didn’t give me any

indication that it was being stressed too much and easily held up to

the bow’s finished draw weight of 65# at a 30" draw.

(photo

4): Tillered at 22 inches and 30 inches of draw (photo

4): Tillered at 22 inches and 30 inches of draw

The final dimensions of the bow turned out to be 69" long overall,

with limbs 1¼" wide tapering to 3/8" nocks. The bow

took a bit of set tillering it out but still came out to the above mentioned

65# @ 30" of draw. Test-shooting it was surprisingly pleasant. It

had very little hand shock, and I was quite pleased at how well the bow

shot on target. Performance was not spectacular but more than adequate

and it shot the 550 grain, 30" arrows spined at 55# extremely well.

I applied a little bit of Forest Green spray enamel paint to hide the

unsightly color of the fiberglass and then I permanently glued the lower

limb into the handle with epoxy. A little bit of rasping and sanding

of the nocks and fades with a final sanding of the limbs, then an alternating

finish of Tung oil and shellac for the limbs and this bow was done (photos

5–7).

I’ve shot the bow many times since I finished it and I am always

pleased with how well it shoots. If you are thinking of building yourself

a two-piece takedown, perhaps you should consider this buildalong. The

most interesting aspect of this type of takedown is that it could be

made with a reflexed handle or a deflex handle just as easily as with

a straight handle. This gives one the ability to make different styles

of takedown bows.

|