|

I believe that every Traditional Archer should know at least

a little bit about archery history. It’s fascinating, and

knowledge of the early archers and their equipment adds a useful

dimension to a contemporary bowhunter’s appreciation of his

sport. I believe that every Traditional Archer should know at least

a little bit about archery history. It’s fascinating, and

knowledge of the early archers and their equipment adds a useful

dimension to a contemporary bowhunter’s appreciation of his

sport.

The bow and arrow go back at least 25,000 years. It was

about then that some inventive prehistoric hunter discovered that

he could subdue an enemy or put meat on the table by shooting a

pointed missile propelled by a taut length of sinew tied to a bent

limb.

For centuries archers cut a groove in

one end of the arrow to accept the bowstring, until the ancient

Egyptians began using a version of our plastic arrow nock. Their

arrow smiths fitted a slotted piece of carved bone on the rear

end of an arrow made of a reed from the shores of the Nile River.

The Persians too were noted bowmen and bowyers. To strengthen their

weapons, the Persians used layers of animal horn and sinew as backing

on their bows.

The Turks were so advanced in their archery technology that

they were able to establish distanceshooting records that were

never equaled. The Turks’ bows and their

skill in shooting were one of the reasons for the failure of the

Crusades in the 12th and 13th centuries. Thousands of Richard the

Lion-Hearted’s

men, equipped only with lances and swords for close combat, fell

to Turkish Bowmen. Another group of fierce bowmen were Attila’s

Huns. Because the Huns were mounted, they used short powerful bows

that could be shot while riding a galloping horse. Sweeping through

Europe in the middle of the Fifth Century, the Huns spread death

and destruction wherever they went. Our modern Traditional Archery

culture and much of our approach to shooting a bow go back to the

great English Longbowmen. It’s interesting to note, however,

that the modern laminated recurve bow with its flat limbs is more

similar to the bows shot by early archers in the eastern Mediterranean. The Turks were so advanced in their archery technology that

they were able to establish distanceshooting records that were

never equaled. The Turks’ bows and their

skill in shooting were one of the reasons for the failure of the

Crusades in the 12th and 13th centuries. Thousands of Richard the

Lion-Hearted’s

men, equipped only with lances and swords for close combat, fell

to Turkish Bowmen. Another group of fierce bowmen were Attila’s

Huns. Because the Huns were mounted, they used short powerful bows

that could be shot while riding a galloping horse. Sweeping through

Europe in the middle of the Fifth Century, the Huns spread death

and destruction wherever they went. Our modern Traditional Archery

culture and much of our approach to shooting a bow go back to the

great English Longbowmen. It’s interesting to note, however,

that the modern laminated recurve bow with its flat limbs is more

similar to the bows shot by early archers in the eastern Mediterranean.

The

old English Longbow was about six feet long, did not have curved

tips and was usually made of solid yew wood. Instead of being flat

the limbs were oval or almost round in cross-section.

The shooting

form used by archers today goes back to the time of England’s

King Henry VIII. So important was archery militarily then that

every able-bodied man was required by law to have a bow and a supply

of arrows, and to practice with them regularly on the village green.

The robust King Henry was an archery buff and quite an archer himself.

He commissioned a scholar, who was also in the tutor of the future

Queen Elizabeth I, to write a treatise setting forth the correct

procedure for shooting a bow. The scholar was Sir Roger Ascham;

the book was called “Toxophilus,” the Greek word for

an archery enthusiast. It was the first instruction manual on archery

form and in a general way is still the basis of the bow-shooting

technique used by Traditional Archers today.

Ascham separated the

shooting process into five steps: standing, nocking, drawing, holding,

and releasing. Even after some 500 years, modern archery instructors

still teach their students to master those five basic steps. In

modern times two more elements have been added, aiming and follow-through,

both of which are related to Ascham’s original five steps.

Aiming is part of the holding step, and follow-through is the final

act in the release. Not many archers in this new millennium year

know that bows and arrows were proposed as a supplement to our

arsenal in the Revolutionary War. Ascham separated the

shooting process into five steps: standing, nocking, drawing, holding,

and releasing. Even after some 500 years, modern archery instructors

still teach their students to master those five basic steps. In

modern times two more elements have been added, aiming and follow-through,

both of which are related to Ascham’s original five steps.

Aiming is part of the holding step, and follow-through is the final

act in the release. Not many archers in this new millennium year

know that bows and arrows were proposed as a supplement to our

arsenal in the Revolutionary War.

By that time the bow as a serious military weapon was dead,

but canny Ben Franklin suggested to one of

George Washington’s generals that the Continental Army include

archery gear in its armament. “I would add bows and arrows.” Franklin

wrote. “These were good weapons not wisely laid aside.” Apparently

his suggestion was not taken seriously; there’s no record

of Colonial forces shooting at Redcoats with arrows.

There were

no known archers in the Civil War engagements. The only instance

of archery activity at that time was at a boys’ prep school,

where the students were trained in the use of the bow as an emergency

measure against marauding soldiers.

There was an important archery development just after the

Civil War. Two Confederate veterans, Maurice and Will Thompson,

lived off the land for two years in the wilds of the Okefenokee

Swamp in Georgia and with them was a former slave, Thomas Williams.

Williams for some reason knew something about English-Style Archery

and showed the two brothers the correct approach to shooting form. There was an important archery development just after the

Civil War. Two Confederate veterans, Maurice and Will Thompson,

lived off the land for two years in the wilds of the Okefenokee

Swamp in Georgia and with them was a former slave, Thomas Williams.

Williams for some reason knew something about English-Style Archery

and showed the two brothers the correct approach to shooting form.

The

Thompson’s bagged a number of deer, two cougars, and a 300-pound

black bear, plus squirrels, rabbits, quail, woodcock, turkeys,

geese, bobcats, raccoons, turtles, and alligators. For smallgame

the brother used straight-limb bows of 30 to 40 pound draw weight;

on larger quarry their straight bows drew at 50 to 75 pounds. The

key to the Thompson’s’ bow hunting success was that

they shot almost daily and learned how to go unnoticed by wild

animals. The two probably were the first white bowhunters to know

the importance of wearing dark clothes to blend in with the cover,

and to use ferns and brush concealment. Modern bowmen would do

well to emulate their tactics.

Maurice wrote a book about his adventures, “The Witchery

of Archery.” It became a best seller, and the exploits of

the two brothers stimulated widespread interest in shooting the

bow. In 1879 the National Archery Association was formed with Will

Thompson as its first president. By the early 1900s, however, interest

in archery had subsided and become more of a social recreation

than an important competitive sport. Hunting big-game animals with

a bow was as extinct as Hiawatha. Then, in 1911, began a remarkable

series of incidents that boosted bow-hunting’s important

position among outdoor sports. Maurice wrote a book about his adventures, “The Witchery

of Archery.” It became a best seller, and the exploits of

the two brothers stimulated widespread interest in shooting the

bow. In 1879 the National Archery Association was formed with Will

Thompson as its first president. By the early 1900s, however, interest

in archery had subsided and become more of a social recreation

than an important competitive sport. Hunting big-game animals with

a bow was as extinct as Hiawatha. Then, in 1911, began a remarkable

series of incidents that boosted bow-hunting’s important

position among outdoor sports.

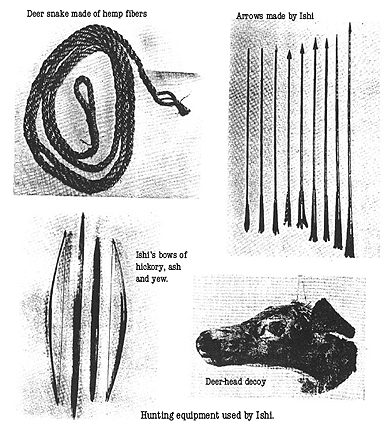

In that year the last known primitive

Indian archerhunter “surrendered” in California. The

Indian, Ishi, was the lone survivor of the Yahi, or Yana, tribe.

Billed as a living stone-age man, he was taken to the University

of California at Berkeley, where anthropologists studied him. Dr.

Saxon Pope, an instructor of surgery at the university’s

medical school, was given the job of attending to Ishi’s

health needs. Pope became fascinated by the Indian’s bow

hunting prowess, and Ishi taught him how to make and use bows and

arrows. The story is told in greater detail in Pope’s book, “Hunting

with the Bow and Arrow,” first published in 1923. Today’s

bowhunters can learn much from Pope’s book.

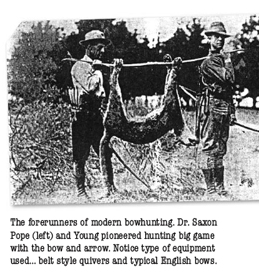

Another sportsman, Arthur Young, joined Pope. Hunting together

and independently, the two friends bagged deer, grizzly bears,

and other big game in Alaska and Africa. Their exploits popularized

the sport of Traditional Bow hunting, as we know it today. Because

they were the first modern white men to use the bow effectively

in hunting, the Pope and Young Club was named in their memory.

But some of the hunting methods used by Ishi, Pope’s Indian

teacher, have not been improved upon to this day. Pope found that

Ishi’s shooting was much sharper on game than on bull’s-eye

targets.

He preferred short shots on small game and set a maximum

of 32 yards for shots at deer. By pressing his mouth against his

hand and blowing, Ishi could produce a call that lured into bow

range cottontails, jackrabbits, bobcats, squirrels, coyotes, foxes,

and lynx. And he could recognize the types of habitat each species

prefers. He proved to Dr. Pope that he could tell by the tones

of a squirrel’s bark whether the animal was scolding a man,

a fox, a hawk, or a bobcat. Ishi’s sense of smell was so

keen that he could actually scent deer, cougars, and foxes. He preferred short shots on small game and set a maximum

of 32 yards for shots at deer. By pressing his mouth against his

hand and blowing, Ishi could produce a call that lured into bow

range cottontails, jackrabbits, bobcats, squirrels, coyotes, foxes,

and lynx. And he could recognize the types of habitat each species

prefers. He proved to Dr. Pope that he could tell by the tones

of a squirrel’s bark whether the animal was scolding a man,

a fox, a hawk, or a bobcat. Ishi’s sense of smell was so

keen that he could actually scent deer, cougars, and foxes.

Most good modern bowhunters are fairly alert with their

eyes and ears, but not many of us try to use our noses the way

an animal does. However, I’ve known a few woodsmen who consistently

could smell out foxes and deer. (My good friend Norm Blaker would

be a good example of someone with this long forgotten ability).

The lesson here seems to be that we should learn to use all of

our senses while in the field.

From the moment he entered the woods Ishi was alert for

game, anticipating that some animal was lurking behind every bush.

He carefully scouted the terrain of the hunting area, noting its

conformation, the location of thickets and woods and the feeding

and bedding ground. He knew that deer are not so active in daylight

hours during full-moon periods. After checking the prevailing wind

direction, Ishi always hunted into the wind and positioned his

blind with the wind in mind. With each slow step, Ishi looked twice.

When he came to the top of a rise, he crawled to the crest and,

with only the top of his head showing, thoroughly checked out the

ground ahead for any movement or unusual color. In early morning

or late afternoon he made a practice of keeping between the sun

and the game that he was tracking. Ishi frequently preferred to

hunt from a blind near a deer trail. One of his tricks was to place

a stuffed buck’s head over his head like a cap, using the

device to attract the curiosity of the deer. Because of the wide

and increasing popularity of bow hunting today, this is one practice

the modern bowhunter would be well advised to avoid. From the moment he entered the woods Ishi was alert for

game, anticipating that some animal was lurking behind every bush.

He carefully scouted the terrain of the hunting area, noting its

conformation, the location of thickets and woods and the feeding

and bedding ground. He knew that deer are not so active in daylight

hours during full-moon periods. After checking the prevailing wind

direction, Ishi always hunted into the wind and positioned his

blind with the wind in mind. With each slow step, Ishi looked twice.

When he came to the top of a rise, he crawled to the crest and,

with only the top of his head showing, thoroughly checked out the

ground ahead for any movement or unusual color. In early morning

or late afternoon he made a practice of keeping between the sun

and the game that he was tracking. Ishi frequently preferred to

hunt from a blind near a deer trail. One of his tricks was to place

a stuffed buck’s head over his head like a cap, using the

device to attract the curiosity of the deer. Because of the wide

and increasing popularity of bow hunting today, this is one practice

the modern bowhunter would be well advised to avoid.

It’s doubtful that bowhunters today would follow Ishi’s

preparations for a hunt, although there’s something to be

gained by considering them. It’s hard to imagine a hunting

archer fasting before a hunt, yet that’s what Ishi did. One

reason was that with no pre hunt victuals; his breath would not

carry the scent of human food. Another reason for not eating was

that he would not have an urge to empty his bowels and thus create

an odor that would signal to nearby animals that a human being

was lurking in their environment. It’s doubtful that bowhunters today would follow Ishi’s

preparations for a hunt, although there’s something to be

gained by considering them. It’s hard to imagine a hunting

archer fasting before a hunt, yet that’s what Ishi did. One

reason was that with no pre hunt victuals; his breath would not

carry the scent of human food. Another reason for not eating was

that he would not have an urge to empty his bowels and thus create

an odor that would signal to nearby animals that a human being

was lurking in their environment.

Before his hunt Ishi took a bath

in a mountain stream, and then rubbed himself with aromatic leaves

to mask his body scent. While hunting, Ishi wore only a loincloth.

Because of his dark skin he wasn’t readily detected by game,

and he didn’t have to worry about clothes interfering with

his bowstring and hanging up on brush.

It’s not recommended

that modern bowmen copy Ishi’s archery form. He used the

Mongolian release in which the string is drawn by the curled thumb.

It’s interesting to note that the Yanas apparently were one

of the few Indian tribes to use this technique.

One passage in Saxon

Pope’s book is strangely prophetic: “It is also futile

to prophesize the future of the bow and arrow. As an implement

of the chase, to us it seems to hold a place unique for fairness.

And in the future development of the wild game problem, where apparently

large game preserves and refuges will be the order of the day,

the bow is a more fitting weapon with which to slay a beast than

a gun or any more powerful agent that may be invented.” Of

course, there are those who say that all hunting should cease,

and that photography and nature study alone should be directed

towards wildlife. Hopefully that day will never come. But at least

no man can consistently decry hunting that eats meat, wears furs

or leather, or uses any vestige of animal tissue, for he is party

to animal killing, and killing more brutal and ignoble than that

of the chase One passage in Saxon

Pope’s book is strangely prophetic: “It is also futile

to prophesize the future of the bow and arrow. As an implement

of the chase, to us it seems to hold a place unique for fairness.

And in the future development of the wild game problem, where apparently

large game preserves and refuges will be the order of the day,

the bow is a more fitting weapon with which to slay a beast than

a gun or any more powerful agent that may be invented.” Of

course, there are those who say that all hunting should cease,

and that photography and nature study alone should be directed

towards wildlife. Hopefully that day will never come. But at least

no man can consistently decry hunting that eats meat, wears furs

or leather, or uses any vestige of animal tissue, for he is party

to animal killing, and killing more brutal and ignoble than that

of the chase

|