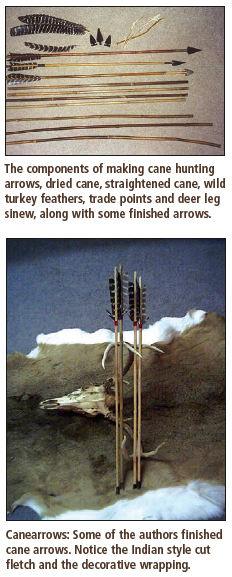

|

There’s an old Indian saying, which I’ll paraphrase. “Making

a good bow is easy, but making a good arrow heap much work.” Not

sure who should be credited with this profound statement, but whoever

it was obviously had considerable experience making arrows from natural

materials. By natural materials I mean materials found growing wild in

nature locally in the area where you live. There’s an old Indian saying, which I’ll paraphrase. “Making

a good bow is easy, but making a good arrow heap much work.” Not

sure who should be credited with this profound statement, but whoever

it was obviously had considerable experience making arrows from natural

materials. By natural materials I mean materials found growing wild in

nature locally in the area where you live.

We spend a lot of time learning to craft good shooting,

durable wooden bows but most fledgling wood bowyers opt for “store

bought” arrow shafting. Most often the same parallel cedar shafting

that they used with their glass backed recurves or longbows. Although

cedar makes a wonderful shaft, comes weighed, spined and more or less

straight, there are other more “natural” options available

which make perfectly good arrows with just a little work…well

a lot of work actually.

Don’t be discouraged though, making your own arrow

shafting is as rewarding as making your own bows, and is part of the

entire self sufficiency process. Another great benefit is this arrow

shafting material is generally free for the taking for anyone willing

to seek it out. It’s possible to make arrows from blocks of wood,

cut into 3/8-inch squares with a table saw and then using a hand plane

to make the four sides into eight sides, then the eight sides into 16

sides, which for all practical purposes is round, and then sanding smooth,

but in this article we are talking about taking plant material that grows

naturally round or tubular to begin with and converting it into arrows.

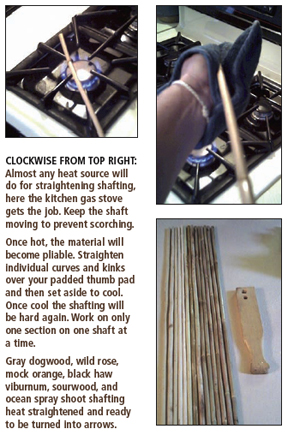

I have made serviceable arrow shafts from river cane, switch cane, and

shoots or branches from gray dogwood, wild rose, mock orange, black haw

viburnum, sourwood, ocean spray and many others. I have also wasted time

making arrows from natural materials that were not suited for arrow shafting

due to weight or strength such as some of the other viburnum species

and horseweed. Just as with making bows, experimentation is half the

fun. The process for making any natural tubular material into an arrow

is the same with minor variations, so I will try to cover them both where

there are any differences.

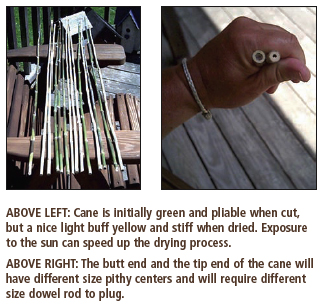

My number-one favorite natural arrow shaft

material is river cane (Arundinaria gigantea) or it’s

slightly smaller cousin switch cane (A. tecta). Both are bamboos

that belong to the grass family Gramineae. Cane grows wild

in large colonies along stream and river edges, and in moist bottom

lands. The river cane tends to grow both in diameter and height than

the switch cane, but both make wonderful arrows. The advantage of using

one of these over the other natural shaft materials is their incredible

strength, their naturally protective waterproof outer casing, and the

fact that they are naturally tapered from one end to the other. The

natural tapering provides for an arrow that tends to clear the riser

better, which is a major considerationwhen shooting non center-shot

bows like our self bows.

I also find it helpful that they grow in colonies or patches

so that when you do find a patch you can gather

many arrow shafts from the same place, rather than trying to locate a

suitable size shoot or branch here or there. Another plus is that you

can return to the same patch year after year to collect additional shafts

as needed.

Another natural shaft material that grows “abundantly” is

multiflora rose. Multiflora is an invasive wild rose shrub found throughout

the Midwest, originally brought in from Asia for weed control and for

small animal cover. It makes a good hard durable arrow but it is impossible

to get rid of the warts from the thorns. They will still shoot straight,

but they will have a lot of “character” to them as it were. Another natural shaft material that grows “abundantly” is

multiflora rose. Multiflora is an invasive wild rose shrub found throughout

the Midwest, originally brought in from Asia for weed control and for

small animal cover. It makes a good hard durable arrow but it is impossible

to get rid of the warts from the thorns. They will still shoot straight,

but they will have a lot of “character” to them as it were.

Once

you find a patch of suitable arrow shaft material it is time to harvest

some. For cane or rose you will need strong sharp clippers, and in the

case of the rose, some heavy gloves and a heavy jacket will prevent a

lot of your blood being spilled while gathering shafts. For branches

or shoots you will need a small hand saw.

For cane, look for a shaft about

the size of an 11/32-inch arrow shaft in the middle portion of your length

of cane. This will leave the tip slightly larger and the nock end slightly

smaller than your 11/32-inch shaft. On the other materials you will want

a shaft slightly larger than that as the diameter will be reduced after

you scrape off the bark.

Regardless of material, you will want to cut your proposed

shaft longer than what you think you are going to need. Remember natural

material arrows tend to shoot well if they are left a little long. So

if you want an arrow for a 27- or 28-inch draw, it doesn’t hurt

to cut your shoots a full 36 inches long or more. Better to have them

too long and cut some off later than cut them too short. My friend Ron

Thompson of Ohio who turned me on to rose shafting suggests you cut them

at least a foot longer than what you think you’ll need. This also

allows for some end splitting while drying.

Once you have a dozen or so pieces cut, on the rose shafts

you will want to cut off all the thorns first. On all the shafts except

the cane you will then take a pocket knife and sit down and scrape

off all the bark. Hold the knife blade at a 90 degree angle to the surface

and scrape away from you removing all bark until the shafts are clean

and white. On the cane shafting you will want to cut off any remnants

of the flower or leaf from the nodes. Once this is done you can go

ahead and do some initial straightening by hand while the sticks are

still green and soft by bending the major curves in the cane or shoot

against your palm until they are reasonably straight. Don’t try

to get them perfectly straight as they will only warp again while drying.

Just try to get some of the major bends kind of straight. Next take a dozen

or so, bundle them up with twine, and throw them in a warm dry spot to

dry out. This can take anywhere from 90 days to 6 storage location, ambient

temperature, and relative humidity. Check them periodically but you will

know when they are dry. Instead of being soft and pliable they will be

hard like, well, arrow shafts… only really crooked arrow shafts.

Cut

the binding to release these new raw arrow shafts and let the fun begin.

First of all you will want to cut them to length. Remember what I said

above about longer arrows flying better? So, if you normally use a 28-inch

b.o.p. arrow, let’s start with cutting them 32 inches long. Examine

each shaft before you cut to get the most appropriate 32 inches of material.

You can always shorten them later if desired, but if you cut them too

short to account for your self-nock and trade slot to begin with you’re

going to be really unhappy later. Remember you are going to want enough

material for a self-nock at one end. It’s better to have too large

of tip end than to have not enough material in the nock end. If you were

careful in raw shaft selection, this shouldn’t be a problem though.

In

order to make these shafts fly straight, we are going to have to straighten

them. For rose and shoot shafts we will generally be dealing with larger

bends, but in the case of the river cane or switch cane we can be dealing

with major internodal bends plus kinks at the nodes, often in different

directions. Trying to straighten any of the shafts or bends without heat

is futile. Heat softens the shaft allowing it to be re-bent, which then

hardens again as it cools. I have straightened shafts over candles, open

campfires, over Coleman heat gun and with a propane torch, but my favorite

is over the burner on our gas stove in the kitchen. Heat is heat. Some

guys will use oil, almost any kind of cooking oil, to coat the shafts.

This helps the shaft absorb heat more evenly and helps prevent scorching.

I forego the oil and just keep the shaft moving over the heat source

so as not to scorch it.  I like to work on six or so shafts at a time. Select one

of the shafts and hold one end up just below your eye sighting down the

shaft looking fo the bends. Pick out one individual bend in that shaft

and see which way you need to apply pressure to remove the bend. Then

heat the shaft in just that area. Remember keep it moving, rolling side

to side as you move it back and forth over the heat source. When the

shaft softens, remove the bend by applying pressure where needed either

over your padded palm or with your two thumbs and then set aside to cool.

Select shaft number two and repeat. Then number three and so on. Wor

on one bend on one shaft at a time. After you have fixed that one bend,

set aside and work on the next shaft. You cannot remove all the bends

in a shaft in a single heating session. It often takes up to a half dozen

sessions to straighten a shaft completely. So in the course of straightening

half a dozen shafts you may heat and straighten bends in each of them

half a dozen times each. Get them as straight as you can, but they don’t

have to be perfect. In the end you will be surprised how straight you

can get some gnarly old sticks, often rivaling the “store bought” cedars.

One thing to keep in mind is, as long as the tip and nock are in line

longitudinally, the shaft can be somewhat crooked in between and still

fly straight. At first this doesn’t make sense. After all the “modern

arrow manufacturers” have been telling you for years that arrows

must not have any out of roundness and often quote how close to being

perfectly round their arrows are, and that you need that for shooting

straight. Then again the “modern bow manufacturers” have

been telling you that you need 80-percent let off, and a straight line

string path, and split limb technology and all manner of things or you

won’t be able to shoot straight either. Since you are reading this

magazine I take it you don’t automatically buy into everything

these manufactures tell you. Still, believing that arrows don’t

have to be “perfectly straight” to fly straight is one of

the hardest sells in primitive archery. I like to work on six or so shafts at a time. Select one

of the shafts and hold one end up just below your eye sighting down the

shaft looking fo the bends. Pick out one individual bend in that shaft

and see which way you need to apply pressure to remove the bend. Then

heat the shaft in just that area. Remember keep it moving, rolling side

to side as you move it back and forth over the heat source. When the

shaft softens, remove the bend by applying pressure where needed either

over your padded palm or with your two thumbs and then set aside to cool.

Select shaft number two and repeat. Then number three and so on. Wor

on one bend on one shaft at a time. After you have fixed that one bend,

set aside and work on the next shaft. You cannot remove all the bends

in a shaft in a single heating session. It often takes up to a half dozen

sessions to straighten a shaft completely. So in the course of straightening

half a dozen shafts you may heat and straighten bends in each of them

half a dozen times each. Get them as straight as you can, but they don’t

have to be perfect. In the end you will be surprised how straight you

can get some gnarly old sticks, often rivaling the “store bought” cedars.

One thing to keep in mind is, as long as the tip and nock are in line

longitudinally, the shaft can be somewhat crooked in between and still

fly straight. At first this doesn’t make sense. After all the “modern

arrow manufacturers” have been telling you for years that arrows

must not have any out of roundness and often quote how close to being

perfectly round their arrows are, and that you need that for shooting

straight. Then again the “modern bow manufacturers” have

been telling you that you need 80-percent let off, and a straight line

string path, and split limb technology and all manner of things or you

won’t be able to shoot straight either. Since you are reading this

magazine I take it you don’t automatically buy into everything

these manufactures tell you. Still, believing that arrows don’t

have to be “perfectly straight” to fly straight is one of

the hardest sells in primitive archery.

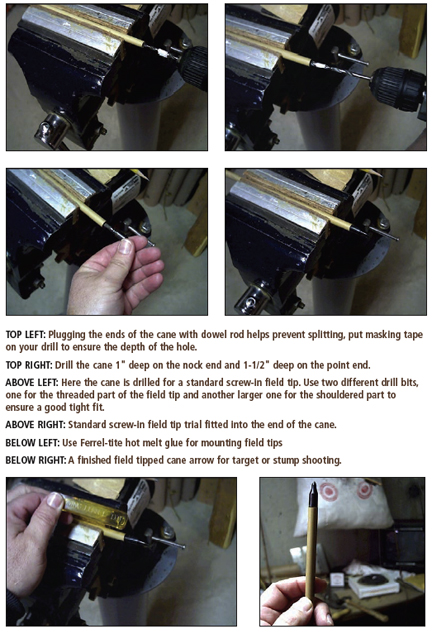

OK, back to arrow making. Believe it or not we’re

almost done. We have straightened our shafts and are about ready to turn

them into arrows. For the cane arrow we will want to knock off the high

points of the node. Do not take them all the way down even with the internodal

cane, just smooth them out some. Use a small file or sandpaper. The small

node bumps won’t hurt a thingand the arrow will still fly well.

Since cane is more or less hollow I like to plug the nock and tip ends

with hardwood doweling. Using the appropriate size drill that matches

the doweling, without weakening the outer shell of the cane, I drill

the nock end 1 inch deep and the tip end 1-1/2 inch deep and using Titebond

II wood glue, glue in pre-cut sections of dowel. The nock end dowel will

naturally be smaller than the tip end dowel. This doweling is available

at nearly any hardwood store or hobby shop. (By the way many primitive

archers make arrows out of the larger sizes of doweling at the hardware

stores. They are often referred to as Ramin wood arrows). The other shaft

materials won’t need this doweling unless the pith line in the

center of the shaft is too large to allow proper tapering of the tip. OK, back to arrow making. Believe it or not we’re

almost done. We have straightened our shafts and are about ready to turn

them into arrows. For the cane arrow we will want to knock off the high

points of the node. Do not take them all the way down even with the internodal

cane, just smooth them out some. Use a small file or sandpaper. The small

node bumps won’t hurt a thingand the arrow will still fly well.

Since cane is more or less hollow I like to plug the nock and tip ends

with hardwood doweling. Using the appropriate size drill that matches

the doweling, without weakening the outer shell of the cane, I drill

the nock end 1 inch deep and the tip end 1-1/2 inch deep and using Titebond

II wood glue, glue in pre-cut sections of dowel. The nock end dowel will

naturally be smaller than the tip end dowel. This doweling is available

at nearly any hardwood store or hobby shop. (By the way many primitive

archers make arrows out of the larger sizes of doweling at the hardware

stores. They are often referred to as Ramin wood arrows). The other shaft

materials won’t need this doweling unless the pith line in the

center of the shaft is too large to allow proper tapering of the tip.

To

finish our primitive arrows we can now cut selfnock slots, cut trade

point slots, or slots for flint heads, or taper the tip for a manufactured

head. Fletch as you would any other shaft material paying attention to

put the cock feather on opposite the stiffest side of the shaft. You

can use precut manufactured feathers, but why not go all the way and

use my favorite, hand stripped turkey feathers. Use your favorite fletching

glue, or fletch tape or if you want to get really primitive, hide glue

and spiral wrapped thread. When using fletch tape you will want to lightly

sand the fletching area on cane arrows to break the glaze to give the

glue or tape something to grip to. When you cut your selfnocks, be sure

to wrap the shaft ahead of the nock to prevent splitting and also wrap

the leading edge of your fletching to help hold it down and to make it

look sharp. Use colored thread covered with glue for decorative purposes

or sinew and hide glue for a more primitive look. Once you have fletched

the shafts, cut your nocks, and mounted your heads, you can seal the

arrows with some Birchwood Casey Tru-Oil or tung oil. I usually put on

three or four coats. You do not have to seal the cane shafting as the

hard outer coating is already waterproof.

If you find at any time that

a bend has returned in any of your shafts, a little heat and some pressure

will make it straight again. Often the heat from just rubbing your palm

on it briskly will be enough to allow you to fix that stubborn spot.

Here’s

something to think about, man has been making arrows in this manner and

killing critters for sustenance for many thousands of years. If it was

good enough for them it should be good enough for you. I can tell you

it’s

been good enough for me. Using arrows made in this manner I have killed

turkeys, wild hogs, javelina and white-tailed deer, plus a pile of small

game.

Yes, making natural material arrows is very labor intensive,

but it should be a labor of love, taking you one step closer to being

self sufficient as a bow hunter and as a “primitive archer” (like

the name of this

magazine you bought). Remember, like the words of wisdom that our Indian

friend left us with, “Making a good bow is easy, but making a good

arrow heap much work.”

|